Rising suicide rate among Hispanics worries community leaders

If you or someone you know may be experiencing a mental health crisis, contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by dialing or texting “988.”

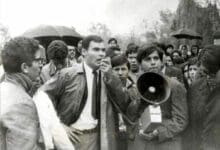

DALTON, Ga. ― A group from teens to seniors gathered in an office inside a grocery store, where Spanish-language food signs cater to the large Hispanic population in this northwestern Georgia city dominated by the carpet industry.

The conversation, moderated by community leader America Gruner, focused on mental health and suicide. The Tuesday night meetings draw about a dozen people, who sit on makeshift furniture and tell their often emotional stories. Gruner formed the support group in 2019 after three Latinos ages 17 to 22 died by suicide here over a two-week period.

“We couldn’t wait for research,” said Gruner, founder and president of the Coalición de Líderes Latinos. “We wanted to do something about it.”

The suicide rate for Hispanic people in the United States has increased significantly over the past decade. The trend has community leaders worried: Even elementary school-aged Hispanic children have tried to harm themselves or expressed suicidal thoughts.

Community leaders and mental health researchers say the pandemic hit young Hispanics especially hard. Immigrant children are often expected to take more responsibility when their parents don’t speak English ― even if they themselves aren’t fluent. Many live in poorer households with some or all family members without legal residency. And cultural barriers and language may prevent many from seeking care in a mental health system that already has spotty access to services.

“Being able to talk about painful things in a language that you are comfortable with is a really specific type of healing,” said Alejandra Vargas, a bilingual Spanish program coordinator for the Suicide Prevention Center at Didi Hirsch Mental Health Services in Los Angeles.

“When we answer the calls in Spanish, you can hear that relief on the other end,” she said. “That, ‘Yes, they’re going to understand me.’”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s provisional data for 2022 shows a record high of nearly 50,000 suicide deaths for all racial and ethnic groups.

Grim statistics from KFF show that the rise in the suicide death rate has been more pronounced among communities of color: From 2011 to 2021, the suicide rate among Hispanics jumped from 5.7 per 100,000 people to 7.9 per 100,000, according to the data.

For Hispanic children 12 and younger, the rate increased 92.3% from 2010 to 2019, according to a study published in the Journal of Community Health.

It’s a problem seen coast to coast, in both urban and rural communities.

The Children’s Institute, a Los Angeles-based social services organization with a primarily Latino clientele, has reported a significant increase in emergency room visits and hospitalizations among young people for risky behavior and suicidal thoughts, said Diane Elias, vice president of behavioral health at the institute. She said children as young as 8 have required hospitalization for attempting to harm themselves.

In Georgia, home to a growing Hispanic population, the suicide rate increased 55% from 2018 to 2022, according to the state Department of Public Health. Ser Familia, a social services organization in metro Atlanta, said it has seen alarming numbers of Hispanic children who report having suicidal thoughts.

“Our kids are interpreters, they pay bills, go to medical appointments,” putting additional stress and anxiety on them, said Belisa Urbina, CEO of Ser Familia.

Suicide is rarely caused by a single issue; many factors can increase one’s risk. These can include a previous suicide attempt, a breakup or loss, a history of depression or other mental illness, financial or job problems, lack of access to health care, and social isolation, said Robin Lee, who leads the Applied Sciences Branch in the CDC’s Division of Injury Prevention.

Mental health experts said there are many social and economic pressures on minority groups. For Hispanics, cultural and systemic obstacles may also be at play.

According to the Latino Community Fund Georgia, stress linked to immigration status has led to an increase in mental health problems.

“Not feeling like you belong, and not knowing what your life holds ahead of you” can create feelings of uncertainty and anxiety, said Vargas, the mental health worker in L.A.

A study of 547 Latino adolescents ages 11 to 16 found the detention or deportation of a family member was associated with significantly higher odds of suicidal thoughts.

“There are waves of immigrants coming as minors, displaced, and sometimes not with immediate caregivers,” Elias said. “This can put hefty burden on children. They are expected, as minors, to balance self-financing and earning money to support family or help them immigrate to the U.S.”

Lack of access to mental health care is a problem for all segments of society, particularly since the beginning of the pandemic. But minorities face added economic and societal obstacles, said Maria Oquendo, a past president of the American Psychiatric Association and a suicide researcher.

Nirmita Panchal, a senior policy analyst for KFF, said children of color “may not receive culturally sensitive mental health screenings, and their mental health symptoms may be mistakenly characterized as disruptive behaviors.”

Language also remains a significant barrier.

“We have a tremendous need for bilingual mental health providers in Georgia,” said Pierluigi Mancini, president and CEO of the Multicultural Development Institute, a Georgia-based consulting organization.

Gruner, who set up the Latino support group in Dalton, said she is aware of only three bilingual providers in that area. The city is in Whitfield County, where more than a third of the 100,000 residents are Hispanic.

And bias can add another obstacle.

A recent Rand Corp. study, using a secret-shopper process, found evidence of potential discrimination during the scheduling process for a mental health appointment in California. About 1 in 5 Spanish-language calls ended with the scheduler hanging up or informing the caller that no one was available to assist in Spanish.

Mental illness can also be culturally taboo among many Black and Hispanic people. (Hispanics can be of any race or combination of races.)

“There is a belief that men shouldn’t seek help — they should solve their problems themselves,” said Francisco, 55, a member of the Dalton support group who himself attempted suicide as a teen. KFF Health News attended the session where he and others spoke, using only their first names for privacy reasons.

To address the mental health crisis, the federal government, in conjunction with states, introduced the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline in 2022 for people to connect with a crisis counselor and other resources. In July, it added a 988 text and chat service in Spanish, but a spokesperson for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration acknowledged more work needs to be done to reach communities at risk.

Across the country, mental health professionals, researchers, and Hispanic leaders point to several ways to reduce suicide.

It’s crucial that more funding goes toward mental health generally, including prevention programs that recognize cultural, legal, and language needs, said Jagdish Khubchandani, a professor and researcher at New Mexico State University.

For now, some local leaders are filling gaps by doing community work, such as forming support groups for the Hispanic population.

Miguel Serricchio of Santa Clarita, California, facilitates bilingual support groups for people whose lives have been rocked by suicide. His son, Alex, battling anxiety, took his own life in 2016 after a breakup with his girlfriend.

“I wanted to get the word out,” Serricchio said.

Gruner, 64, who was born in Mexico City, hears from people in her weekly support group who have thought about suicide, have attempted it, or worry about their children doing the same.

During the meeting attended by KFF Health News, a woman named Angela said her three daughters had anxiety and depression. “One of them told me she is suffering because we are immigrants,” she said.

Another attendee, Katherine, 16, cited, among other factors, unstable living conditions. For a time, she said, “we were struggling to find a home. We would be roommates with other families,” she said.

Her friend Alejandro, also 16, said he’s struggled with suicidal thoughts after the death of his grandmother and arguments between his parents.

Vargas said that young people are looking for honesty and no judgment. They don’t want adults to dismiss their problems, telling them they’ll grow out of them.

“While the subject of suicide can be really scary or unsettling, when someone approaches you and tells you they are thinking about suicide, it can be a really wonderful, beautiful moment of hope,” Vargas said. “That opening is an opportunity to connect and support one another.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.