The poetry of Sappho of Lesbos: it seems like only yesterday

What we know of the life of Sappho of Mytilene, or Sappho of Lesbos, are shreds, shreds in the wind. A few allusions here or there, enough only to reliably determine that yes, she did exist, that she was not a legend, an invention, as some refer to Shakespeare and even to Jesus Christ.

In fact, very little else is known about Sappho. Only the connotations. And the envy.

After all, this Greek poet lived between 650 and 580 BC. That is, about 2,500 years ago. What else do we know? In the Aeolian dialect of her time her name was Psappha or Psafa. And we know that she had a daughter named Cleis. Maybe.

An analysis of her poetry finds it innovative, and so well worked that her literary devices are not even noticeable.

And no much more. We clothe naked Sappho with the ideas, realities and conflicts of our own time. The love of women. Her devotion to divinity. And we assume anything while we enjoy the incredible grace of her verse.

Yes, we make her contemporary even though this era and hers are so different we could have lived on different planets.

But it’s not a true analogy. Poetically we are the children of Sappho. Which should lead us, at least, to listen to what she has to say. Even though most of her work was destroyed by the Catholic Church in the VI Century because of their erotic and lesbian imagery.

One word about the English versions. Or any other translation from the old, local dialect she wrote her poems. A difference of 100 years in the translation changes the meaning of the work from a XIX century to a XXI century poem.

Here they are:

Dead shalt thou lie; and nought

Be told of thee or thought,

For thou hast plucked not of the Muses’ tree:

And even in Hades’ halls

Amidst thy fellow-thralls

No friendly shade thy shade shall company!

And:

You will be underground

never far from you

dead, there will be memory

no longing; what to you

of this rose bush

the Muses give nothing;

ignored too,

you will march

to that infernal mansion,

and flying you will miss,

always without light,

next to the dead you

Sappho lived – that we know, or “know” – on the Greek island of Lesbos, on the eastern shore of the Aegean Sea. Apart from that, and many fragments of her poems, we have nothing. There were no contemporary witnesses of her life, although future generations repeated her words, exalted her memory and longed for her to come back vehemently.

And her fascination for her love for women remains. For some, it was the reason for the fierce persecution she suffered. Three centuries after her life, a censor characterized her as “a whore who sang of her own debauchery.” And 1,500 years later, in 1073, Pope Gregory VII ordered her work to be burned. Again.

But love between women or between men was common and accepted in ancient Greece, especially among the wealthiest, who, after all, could buy, or maintain, or attract young men or maidens. The change, the rejection, came later, when the Church -any church- got into our beds. The ideas or morality inculcated by the Church, considered love as perversion.

According to some sources though, Sappho was also so disappointed by the rejection by a man, Phaon, that she took her own life, according to Ovid (Ovidius) in this very long fragment of his Ars Amatoria -The Art of Love. Although those who study her doubt it, because such an act would contradict all her way of being throughout her life.

Luckily, according to the Brooklyn Museum, “attempts to revive her poetry began in the Renaissance and have continued throughout history.” We are at the receiving end of this process.

“Eros shook my mind like a mountain wind falling on oak trees.”

― Sappho, If Not, Winter:

We begin, then, with a recent and romantic testimony, like her poems, of that trait of Sappho, magnified with each passing century: The painting “Sappho and Erinna in a garden in Mytilene”, by Simeon Solomon, in 1864.

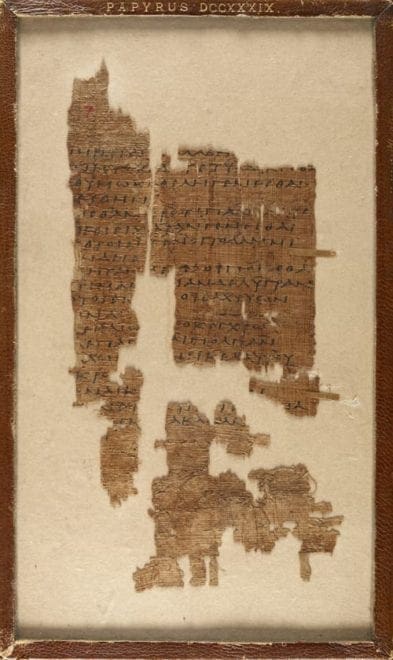

The picture depicts Sappho embracing her fellow poet Erinna in a garden at Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Did she look like that? Of course not. In stark contrast, this is a manuscript in the poet’s own handwriting, which survived in minuscule fragments, like the Dead Sea Scrolls, and is housed in the British Library. One of the most precious finds of its 150 million works.

Hard to imagine so much distance, so much time. And this extraordinary love poem, “Fragment 31”, written in the Aeolic dialect spoken in Sappho’s home island of Lesbos.

“That man seems to me to be equal to the gods

Who is sitting opposite you

And immediately a subtle fire has run over my skin,

I cannot see anything with my eyes,

And my ears are buzzing

A cold sweat comes over me, trembling

Seizes me all over, I am paler

Than grass, and I seem nearly

To have died.

But everything must be dared/endured, since (even a poor man)…”

Sappho’s most famous work is “Ode to Aphrodite”:

Deathless Aphrodite of the spangled mind,

child of Zeus, who twists lures, I beg you

do not break with hard pains,

O lady, my heart

but come here if ever before

you caught my voice far off

and listening left your father’s

golden house and came,

yoking your car. And fine birds brought you,

quick sparrows over the black earth

whipping their wings down the sky

through midair—

they arrive. But you, O blessed one,

smiled in your deathless face

and asked what (now again) I have suffered and why

(now again) I am calling out

and what I want to happen most of all

in my crazy heart. Whom should I persuade (now again)

to lead you back into her love? Who, O

Sappho, is wronging you?

For if she flees, soon she will pursue.

If she refuses gifts, rather will she give them.

If she does not love, soon she will love

even unwilling.

Come to me now: loose me from hard

care and all my heart longs

to accomplish, accomplish. You

be my ally.

How not to fall in love with her, 25 centuries later?

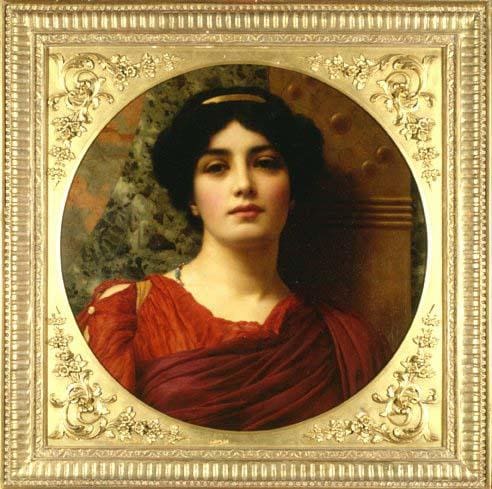

Out of desperation, generations have reproduced her features just as they imagined her, following their own ideas of beauty and mystery.

She is depicted here as dramatic, divine, all-powerful, defiant of the seas and the skies, without letting go of the instrument that accompanied her singing, in 1840.

But according to the most credible sources, she was completely different. She has a round and full face, small and feminine lips, a dreamy and lost look, her hair gathered in elaborate curlers in the style of the time of this sculpture, only some 100 years after her death.

Come Here to Me from Crete

Come here to me from Crete, to your holy temple,

Where your lovely grove of apple stands,

Where the altars smoke with frankincense;

Here cold water sounds through apple branches,

The ground is all carpeted with roses,

Enchanted sleep falls from shimmering leaves;

Here the horse-grazed field

Is lush with spring flowers

And the winds sweetly blow….

Here, Cyprian goddess, you grasp

The golden cup so gracefully,

Pouring like wine the nectar

All-mixed with our rejoicing.

Translated by Peter Saint-Andre

Despite her characterization as a poet of love and desire, much of the work of Sappho of Lesbos is dedicated to her goddess, Aphrodite, the Greek equivalent of Venus. But lets remember that Solomon’s Canticle of Canticles is clearly a cycle of passionate love poems to a woman. Only later it was defined as a collection of hymns to the Creator. The total control of religions transformed it into a code of praise to God, or the gods. Maybe this is also the case and the Aphrodite in Sappho’s poetry is her lover.

Immortal Aphrodite

I

Shimmering-throned immortal Aphrodite,

Daughter of Zeus, Enchantress, I implore thee,

Spare me, O queen, this agony and anguish,

Crush not my spirit

II

Whenever before thou has hearkened to me–

To my voice calling to thee in the distance,

And heeding, thou hast come, leaving thy father’s

Golden dominions,

III

With chariot yoked to thy fleet-winged coursers,

Fluttering swift pinions over earth’s darkness,

And bringing thee through the infinite, gliding

Downwards from heaven,

IV

Then, soon they arrived and thou, blessed goddess,

With divine contenance smiling, didst ask me

What new woe had befallen me now and why,

Thus I had called the.

V

What in my mad heart was my greatest desire,

Who was it now that must feel my allurements,

Who was the fair one that must be persuaded,

Who wronged thee Sappho?

VI

For if now she flees, quickly she shall follow

And if she spurns gifts, soon shall she offer them

Yea, if she knows not love, soon shall she feel it

Even reluctant.

VII

Come then, I pray, grant me surcease from sorrow,

Drive away care, I beseech thee, O goddess

Fulfil for me what I yearn to accomplish,

Be thou my ally.

So what was her like? She was like her poetry. Better to remember her like this. Beautiful, dreamy, distant, unattainable. Better to remember her as our contemporary. Because of her poetry, she is.

Lastly, and only for the sake of graphically seeing her work in modern Greek, the successor to the peculiar dialect of Lesbos in which she wrote.

Ποικιλόθρον᾽ ὰθάνατ᾽ ᾽Αφρόδιτα,

παῖ Δίος, δολόπλοκε, λίσσομαί σε

μή μ᾽ ἄσαισι μήτ᾽ ὀνίαισι δάμνα,

πότνια, θῦμον.

ἀλλά τυίδ᾽ ἔλθ᾽, αἴποτα κἀτέρωτα

τᾶς ἔμας αὔδως αἴοισα πήλγι

ἔκλυες πάτρος δὲ δόμον λίποισα

χρύσιον ἦλθες

ἄρμ᾽ ὐποζεύξαια, κάλοι δέ σ᾽ ἆγον

ὤκεες στροῦθοι περὶ γᾶς μελαίνας

πύκνα δινεῦντες πτέῤ ἀπ᾽ ὠράνω αἴθε

ρος διὰ μέσσω.

αῖψα δ᾽ ἐξίκοντο, σὺ δ᾽, ὦ μάκαιρα

μειδιάσαισ᾽ ἀθανάτῳ προσώπῳ,

ἤρἐ ὄττι δηὖτε πέπονθα κὤττι

δηὖτε κάλημι

κὤττι μοι μάλιστα θέλω γένεσθαι

μαινόλᾳ θύμῳ, τίνα δηὖτε πείθω

μαῖς ἄγην ἐς σὰν φιλότατα τίς τ, ὦ

Ψάπφ᾽, ἀδίκηει;

καὶ γάρ αἰ φεύγει, ταχέως διώξει,

αἰ δὲ δῶρα μὴ δέκετ ἀλλά δώσει,

αἰ δὲ μὴ φίλει ταχέως φιλήσει,

κωὐκ ἐθέλοισα.

ἔλθε μοι καὶ νῦν, χαλεπᾶν δὲ λῦσον

ἐκ μερίμναν ὄσσα δέ μοι τέλεσσαι

θῦμος ἰμμέρρει τέλεσον, σὐ δ᾽ αὔτα

σύμμαχος ἔσσο.